The Russian Library @ 25

by Christine Dunbar

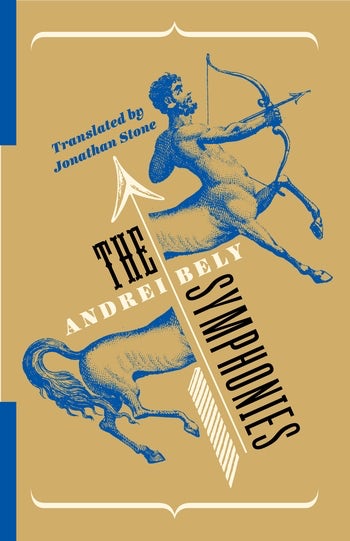

The 2021 publication of Andrei Bely’s The Symphonies, in a translation by Jonathan Stone, has now brought the number of books in Columbia University Press’s Russian Library series to 25. Reviewers have hailed the book for its “otherworldly tales of haunting beauty” and as “a welcome addition to the canon of classic Russian literature in English.”

The 2021 publication of Andrei Bely’s The Symphonies, in a translation by Jonathan Stone, has now brought the number of books in Columbia University Press’s Russian Library series to 25. Reviewers have hailed the book for its “otherworldly tales of haunting beauty” and as “a welcome addition to the canon of classic Russian literature in English.”

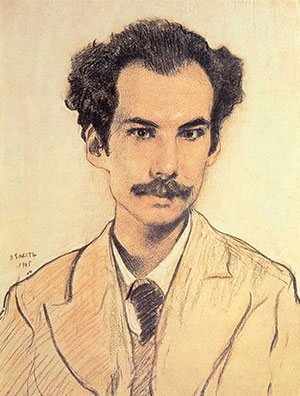

Jon Stone’s scholarly work on Russian Symbolism is highly regarded in the field, but I was skeptical when he contacted me about a translation of Bely’s “Northern Symphony.” Andrei Bely is a major figure in the Russian literary tradition, and the chapter on him in Vladislav Khodasevich’s Necropolis is one of my favorites. (Necropolis appeared in the Russian Library in 2019 in Sarah Vitali’s sharp and meticulous translation.) Bely is known primarily for his novel Petersburg, and the Russian Library is not a completist project. Our goal is to broaden the variety of Russian literature available to entertain, challenge, and inspire the Anglophone reader.

I met with Jon in an empty breakfast room at a Slavic studies conference, delighted to have found a source of tea not yet depleted by the panel-attending hordes. Jon started talking about the “Symphonies,” genre-defying works in which the young Bely worked out his artistic philosophy, and soon I was transported from our mundane surroundings, fascinated by Bely’s seeming ability to inhabit the world of the everyday and the world of myth simultaneously.

There are certain concepts integral to the understanding of modern Russian literature. Important to Bely and his Symbolist milieu are “byt” and “zhiznetvorchestvo.” “Byt,” in the sense I’m thinking of, refers to the oppressiveness of the everyday. As Roman Jakobson puts it in an article about the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, “opposed to [the] creative urge toward a transformed future is the stabilizing force of an immutable present, overlaid, as this present is, by a stagnating slime, which stifles life in its tight, hard mold. The Russian name for this element is byt.” “Zhiznetvorchestvo” is a neologism made up of the words for “life” and “creation”; it refers to the practice of living your life as if it were itself a work of art. In her introduction to To the Stars and Other Stories by Fyodor Sologub, forthcoming in the Russian Library, Susanne Fusso gives as an example “a club of young girls who masquerade as the grieving fiancées of recently deceased men they've never met.”

There are certain concepts integral to the understanding of modern Russian literature. Important to Bely and his Symbolist milieu are “byt” and “zhiznetvorchestvo.” “Byt,” in the sense I’m thinking of, refers to the oppressiveness of the everyday. As Roman Jakobson puts it in an article about the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, “opposed to [the] creative urge toward a transformed future is the stabilizing force of an immutable present, overlaid, as this present is, by a stagnating slime, which stifles life in its tight, hard mold. The Russian name for this element is byt.” “Zhiznetvorchestvo” is a neologism made up of the words for “life” and “creation”; it refers to the practice of living your life as if it were itself a work of art. In her introduction to To the Stars and Other Stories by Fyodor Sologub, forthcoming in the Russian Library, Susanne Fusso gives as an example “a club of young girls who masquerade as the grieving fiancées of recently deceased men they've never met.”

Living your life as if it were a work of art is neither a safe nor necessarily ethical practice. Khodasevich’s Necropolis teams with stories of practitioners of zhiznetvorchestvo who burned bright, burned quickly, and burned many people in their paths before they burned out. Yet in Sologub’s story, the apparent travesty of the playacting girl at the funeral is undercut by the sincerity of her grief. As Jon Stone stresses in his post on the Columbia University Press blog: “Bely believed in myth and magic.” The centaurs, for him, were real.

At the suggestion of the Russian Library Editorial Advisory Board, Jon expanded his translation to include all four of Bely’s “Symphonies.” Unlike the “Northern Symphony,” the subject of our first conversation, the action of the “Dramatic Symphony,” “The Return,” and “A Goblet of Blizzards” occurs in a city that is recognizably Moscow. Yet it is also a place where a bust of Kant turns to life and sticks its tongue out, an eagle can smoke a cigarette, and an abbot flies above the city, pissing snow.

It's now been two years since I have attended an academic conference, a gathering that for me often encompasses the most banal and stultifying aspects of byt—the airless, windowless exhibit hall, the purposefully anonymous corporate décor, the necessity of minding the booth even though everyone is in the sessions for at least another hour. But this mundane background is only one level, one layer of reality. Academic conferences are also where I have conversations with scholars and translators like Jon Stone, conversations that exponentially increase my sense of the possible. Part of the brilliance of Bely’s Symphonies is how he shows us the more real is always there, behind everything. The reader’s job is to learn to see.

The first 25 books in the Russian Library showcase Russian literature’s variety, from The Life Written by Himself, written in an Arctic village in the 1660s and ‘70s by the exiled Archpriest Avvakum, to Linor Goralik’s 21st century flash fiction, short stories, poems, and plays, written and set in Moscow, Tel Aviv, and Jerusalem, and collected in the volume Found Life. Translator Susanne Fusso offers a fresh take on Nikolai Gogol’s short fiction in The Nose and Other Stories, and Nora Favorov brings us a funny, irreverent 19th novel by popular—but nearly forgotten—female author Sofia Khvoshchinskaya: City Folk and Country Folk. And this only scratches the surface of the books published and planned in the series.

Take a look; maybe you, too, will discover a new way to see.

Christine Dunbar is the editor of the Russian Library series at Columbia University Press.