READ RUSSIA PRIZE 2020 shortlisted titles - excerpts

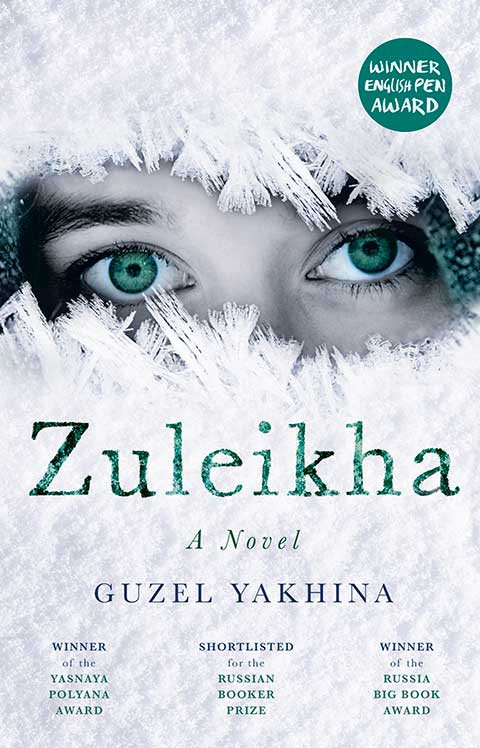

Excerpt: Guzel Yakhina’s “Zuleikha: A Novel”

One time, though, he suddenly stared at her. She felt that gaze without looking up. “Is everything all right?” she asked. “Is the food salted enough?” Ignatov didn’t answer, he just looked. She slipped out and took a breath. As she walked down the path, she sensed that gaze on her neck, in the place where the hair starts to grow. She’s started wearing a headscarf to go to Ignatov’s. And he’s started looking at her. Now the air isn’t even water, it’s becoming honey. Zuleikha is in that honey, gliding, tensing all her muscles and stretching her sinews, but everything’s moving slowly, like in a dream. Try as she might, she cannot possibly move any faster; she wouldn’t be able to even if there was a re. She walks out the door, tired, as if she’s been chopping firewood, and she needs something to drink.

One time, though, he suddenly stared at her. She felt that gaze without looking up. “Is everything all right?” she asked. “Is the food salted enough?” Ignatov didn’t answer, he just looked. She slipped out and took a breath. As she walked down the path, she sensed that gaze on her neck, in the place where the hair starts to grow. She’s started wearing a headscarf to go to Ignatov’s. And he’s started looking at her. Now the air isn’t even water, it’s becoming honey. Zuleikha is in that honey, gliding, tensing all her muscles and stretching her sinews, but everything’s moving slowly, like in a dream. Try as she might, she cannot possibly move any faster; she wouldn’t be able to even if there was a re. She walks out the door, tired, as if she’s been chopping firewood, and she needs something to drink.

She knows what’s happening because Murtaza had looked at her that way many years ago, when the youthful Zuleikha had just come into his house as his wife. Her husband’s killer is looking at her with her husband’s gaze.

If only she didn’t have to go to Ignatov’s, then she could stay out of his sight. But how could she get out of it? She couldn’t send Achkenazi to him with plates. And so she goes, slowly climbing up the path, opening the heavy door, inhaling deeply, and then ducking into the thick, viscous honey. She senses herself, all of her, gradually turning to honey. Her hands, which place the pot on the table and seem to ow along it, her feet, which stride along the floor and seem to stick to it, and her head, which wants to drive her right out of this place but softens, fusing and melting under her very, very tightly tied headscarf.

Her husband’s killer is looking at her with her husband’s gaze and she’s turning to honey. This is agonizing, unbearable, and horrendously shameful. It’s as if all her past and present shame has merged, absorbing everything she hasn’t felt shameful enough about during this mad year: the many nights spent side by side with unknown people, unknown men, in the darkness of dungeons and the crowdedness of the railroad car; her pregnancy, borne in front of others from the first months until the end; and giving birth around people. In order to somehow escape that shame and overcome the improper thoughts, Zuleikha often imagines a large black tent made of thick, crudely dressed sheepskins and resembling Bashkir yurts. The tent covers Ignatov and the commandant’s headquarters like a solid lid, and when the door curtain is drawn at the entrance, everything carnal, shameful, and ugly remains there, inside. Zuleikha leaps on a large Argamak horse, digs him sharply with her bare heels, and speeds away without looking back.